11.

Wines from the edge

This article originally appeared in the August issue of Decanter

Agulhas Wine Triangle: South Africa’s southernmost wines Home to a forceful, ever-present wind, this remarkable region feeds off the elements, allowing them to cool and shape the environment – something winemakers use to their advantage when making South Africa’s southernmost wines. Malu Lambert discovers this unique, extreme region and picks her 12 must-try wines.

There are many places on earth defined by wind. It shapes the landscape – from dunes in deserts to bent trees along the coast, battering all into submission. It also informs viticulture, such as in the Rhône Valley, where vines are trained straight to avoid damage from the dogged Mistral.

Likewise, on the southwest edge of Africa is the Agulhas Wine Triangle, which lies between the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans at the point where the two giant masses meet, and is stalked by ocean gales and the strong wind and rain phenomenon known as the Black Southeaster.

![]()

There are many places on earth defined by wind. It shapes the landscape – from dunes in deserts to bent trees along the coast, battering all into submission. It also informs viticulture, such as in the Rhône Valley, where vines are trained straight to avoid damage from the dogged Mistral.

Likewise, on the southwest edge of Africa is the Agulhas Wine Triangle, which lies between the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans at the point where the two giant masses meet, and is stalked by ocean gales and the strong wind and rain phenomenon known as the Black Southeaster.

Here, the vines clinging to the edge of the continent are under perpetual assault from sea winds that whip along the Strandveld coastline – the resting place, unsurprisingly, of more than 130 shipwrecks.

This daily bombardment naturally limits vine growth, so vineyards here generally produce small yields, suited for quality production. The cooling effects help with acid retention in the grapes and lengthen the ripening period, resulting in more concentrated aroma and flavour development.

The wind dries moisture in the vine canopy, too, lowering disease pressure and allowing more sustainable farming methods.

At the Triangle’s core, the speciality is saline, site-expressive Sauvignon Blanc. Syrah fares well too, manifesting as fine and elegant.

Set within an obtuse triangle taking in Elim and Napier on the western side, Malgas and Swellendam to the east, and Cape Agulhas at the southernmost point, are the 10 members of the Agulhas Wine Triangle – a winemakers’ group established in 2019.

In Elim, this incorporates Black Oystercatcher, Strandveld Vineyards and The Giant Periwinkle as well as producers who source from the area: Trizanne Signature Wines, Ghost Corner and Land’s End. Then there’s Sijnn from Malgas, Olivedale from Swellendam, Lomond from Cape Agulhas and Bruce Jack’s The Drift Estate in Napier.

This daily bombardment naturally limits vine growth, so vineyards here generally produce small yields, suited for quality production. The cooling effects help with acid retention in the grapes and lengthen the ripening period, resulting in more concentrated aroma and flavour development.

The wind dries moisture in the vine canopy, too, lowering disease pressure and allowing more sustainable farming methods.

At the Triangle’s core, the speciality is saline, site-expressive Sauvignon Blanc. Syrah fares well too, manifesting as fine and elegant.

Set within an obtuse triangle taking in Elim and Napier on the western side, Malgas and Swellendam to the east, and Cape Agulhas at the southernmost point, are the 10 members of the Agulhas Wine Triangle – a winemakers’ group established in 2019.

In Elim, this incorporates Black Oystercatcher, Strandveld Vineyards and The Giant Periwinkle as well as producers who source from the area: Trizanne Signature Wines, Ghost Corner and Land’s End. Then there’s Sijnn from Malgas, Olivedale from Swellendam, Lomond from Cape Agulhas and Bruce Jack’s The Drift Estate in Napier.

Trizanne Barnard, winemaker and owner of Trizanne Signature Wines, was drawn both to the cool-climate elegance of Elim’s grapes and to the pioneering spirit of the area.

![]()

‘It has this energy I find nowhere else,’ she says. ‘Every time I enter the Agulhas Plains there’s this incredible light intensity. I’m always struck by it. And you can feel this bright tension in the wines too.’

Losing yourself

Like other famous triangles, Agulhas is easy to disappear in. I discover this for myself on a two-day road trip, following the lines of the Triangle, beginning at its sharpest point, in Swellendam.

The route is punctuated by characters, such as the eccentric Carl van Wijck of Olivedale, who greets us at his cellar door with bare feet (it was not a warm day), declaring: ‘Welcome to the palace of no pretensions!’ His winery is decked out with antiques, paintings and Persian carpets, and classical music is piped through the air. The wines are correspondingly eclectic.

‘It has this energy I find nowhere else,’ she says. ‘Every time I enter the Agulhas Plains there’s this incredible light intensity. I’m always struck by it. And you can feel this bright tension in the wines too.’

Losing yourself

Like other famous triangles, Agulhas is easy to disappear in. I discover this for myself on a two-day road trip, following the lines of the Triangle, beginning at its sharpest point, in Swellendam.

The route is punctuated by characters, such as the eccentric Carl van Wijck of Olivedale, who greets us at his cellar door with bare feet (it was not a warm day), declaring: ‘Welcome to the palace of no pretensions!’ His winery is decked out with antiques, paintings and Persian carpets, and classical music is piped through the air. The wines are correspondingly eclectic.

The range includes a bottling of that teinturier (red-fleshed) South African oddity, Roobernet, a cross between Cabernet Sauvignon and Alicante Bouschet created in the 1960s by Professor Christiaan Johannes Orffer of the University of Stellenbosch. A skin-macerated white, Wild Melody, was particularly appealing.

The trip continues over rolling dirt roads, sucking us ever closer to the coast. To get to Sijnn we have to park on a yellow steel pontoon that chugs across the serpentine Breede river. Sijnn is in Malgas, near the river’s mouth, its terrain characterised by river stones reminiscent of Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s famous galets.

The vineyards share space with orange-tipped aloes and other fynbos; grape-loving birds are a perennial hazard. Owner David Trafford (of De Trafford Wines in Stellenbosch) has handed day-to-day responsibility for viticulture and winemaking to young rising star Charla Bosman. Here, the focus is simply on a red and a white blend, both excellent.

More gravel roads swell beneath us as we make our way west to our home for the night at Black Oystercatcher. Proprietor and winemaker Dirk Human’s family have been farming this land for generations. Built like a rugby player, Human feels as immutable as the landscape, though there’s a finesse and gentle intelligence to his winemaking.

The trip continues over rolling dirt roads, sucking us ever closer to the coast. To get to Sijnn we have to park on a yellow steel pontoon that chugs across the serpentine Breede river. Sijnn is in Malgas, near the river’s mouth, its terrain characterised by river stones reminiscent of Châteauneuf-du-Pape’s famous galets.

The vineyards share space with orange-tipped aloes and other fynbos; grape-loving birds are a perennial hazard. Owner David Trafford (of De Trafford Wines in Stellenbosch) has handed day-to-day responsibility for viticulture and winemaking to young rising star Charla Bosman. Here, the focus is simply on a red and a white blend, both excellent.

More gravel roads swell beneath us as we make our way west to our home for the night at Black Oystercatcher. Proprietor and winemaker Dirk Human’s family have been farming this land for generations. Built like a rugby player, Human feels as immutable as the landscape, though there’s a finesse and gentle intelligence to his winemaking.

︎︎︎

He has a range of wines, including a Shiraz, but it’s the Sauvignon Blancs that impress. Human has made a study of the grape, producing a distinctive three-bottle collection he calls the Secrets of Sauvignon, made from grapes grown on different soil types: iron ferricrete, quartzite and shale.

From wetlands to mountains

The farm also encompasses extensive wetlands, which have been given over to conservation, including a resident pod of hippos. With the hippos keeping to the reeds, we drive through a herd of buffalo, our glasses filled with The Drift’s Penelope Brut Rosé Cap Classique sparkling.

While the wines of Elim are characterised by the sea, The Drift Estate – Bruce Jack’s Napier estate – looms mountainous towards the western tip of the Triangle. Jack describes his farm: ‘It’s at 500m on a north-facing slope. It’s very cool, allowing us to craft wines that are mountain-born: elegant, spicy, savoury and moreish.’

The next day dawns with a crystalline light. The Triangle lies at 34°S – with no obstructions to the flat plains, the sunlight spills over unimpeded.

From wetlands to mountains

The farm also encompasses extensive wetlands, which have been given over to conservation, including a resident pod of hippos. With the hippos keeping to the reeds, we drive through a herd of buffalo, our glasses filled with The Drift’s Penelope Brut Rosé Cap Classique sparkling.

While the wines of Elim are characterised by the sea, The Drift Estate – Bruce Jack’s Napier estate – looms mountainous towards the western tip of the Triangle. Jack describes his farm: ‘It’s at 500m on a north-facing slope. It’s very cool, allowing us to craft wines that are mountain-born: elegant, spicy, savoury and moreish.’

The next day dawns with a crystalline light. The Triangle lies at 34°S – with no obstructions to the flat plains, the sunlight spills over unimpeded.

The tip of Africa

Our next stop is Africa’s southernmost wine estate: Strandveld Vineyards. Conrad Vlok has been winemaker here since 2004. The estate is still relatively boutique – 87ha under vine, the majority of which is Sauvignon Blanc. ‘We currently have an Albariño trial underway, which is showing promise,’ Vlok mentions.

We pull over at the Pofadderbos Vineyard, so named as the highly venomous puff adder has often been spotted here. ‘Most of our vineyards are two decades old and replacement is very important,’ explains Vlok. ‘Due to the extreme weather conditions, our vineyards don’t have a very long productive lifespan – especially the Sauvignon Blanc, which can be affected by dieback. We are continuously planting new vineyards or replacement vines.’From this raw, wild landscape Vlok makes effortlessly elegant wines, expressive of the liminal terroir. The high acidity – an integral part of the structure – extends their longevity. As the wines get older they gain in complexity, the textures becoming silkier and the region’s intrinsic salinity intensifying.

There’s an abundance of storytelling from the town of Baardskeerdersbos, beginning with the name itself. It is based on a myth of small nocturnal spiders called ‘baardscheerders’, or beard shearers, which are said to cut men’s beards while they sleep. Pierre Rabie, winemaker at The Giant Periwinkle, uses this and other local legends as inspiration when naming his wines.

‘I love the Agulhas Plains. I grew up here,’ says Rabie. ‘It’s a privilege to make wine in such a beautiful and remote place – but you have to respect the elements.’

There’s an abundance of storytelling from the town of Baardskeerdersbos, beginning with the name itself. It is based on a myth of small nocturnal spiders called ‘baardscheerders’, or beard shearers, which are said to cut men’s beards while they sleep. Pierre Rabie, winemaker at The Giant Periwinkle, uses this and other local legends as inspiration when naming his wines.

‘I love the Agulhas Plains. I grew up here,’ says Rabie. ‘It’s a privilege to make wine in such a beautiful and remote place – but you have to respect the elements.’

He explains: ‘Agulhas grapes generally have high natural acidities and low pH, which contributes to the distinctive freshness and ageworthiness of the wines. I’ve learned to embrace the acidity and to work with it as opposed to against it.’

Rabie’s Blanc Fumé 2019 has luminous acidity – a scaffolding on which he layers pure fruit with just a hint of smoke from some oak contact in Russian flex cubes.

![]()

Rabie’s Blanc Fumé 2019 has luminous acidity – a scaffolding on which he layers pure fruit with just a hint of smoke from some oak contact in Russian flex cubes.

︎︎︎

Underlying energy

Our final destination is Lomond, further towards the coast. Previously in the portfolio of South African drinks giant Distell, Lomond is now privately owned and there are a number of ambitious projects underway.

This includes a new cellar across the Lomond dam (pictured at the top) featuring solar panels that power both the winery and irrigation of the vineyards, and the Rockpool wine range – based on the idea that rock pools are ever-changing and so will the wines be. The current releases include a Chenin Blanc white and a new-wave style of Mourvèdre red, which is punchy and bright, with just the right amount of structure.

At just 8km from the ocean, the wind is as ever-present here as it is through the rest of the Triangle; shaping, cooling, concentrating. The land feels alive with its own elemental breath.

Bruce Jack captures this feeling: ‘There is an underlying energy in Agulhas that’s impossible to fully grasp or explain. It’s as though the environment is not passive, rather it is an active participant. And this is what sets the wines apart.︎

Bruce Jack captures this feeling: ‘There is an underlying energy in Agulhas that’s impossible to fully grasp or explain. It’s as though the environment is not passive, rather it is an active participant. And this is what sets the wines apart.︎

10.

Lost in the fog

This article originally appeared in Volume 7 of the JAN Journal

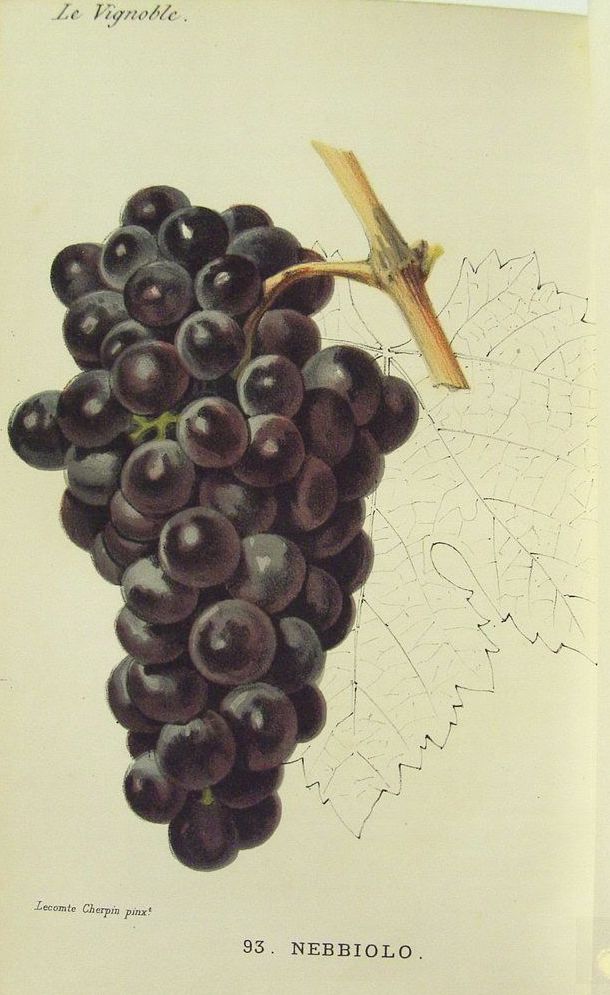

A mystery made of smoke and rose petals. One of the most ancient grape varieties, Nebbiolo brings to mind gilded and soaring Christendom churches, angels carved into flightless motion, the musk of pluming incense. It’s a grape that conjures up the power, prestige and solemnity of the Vatican. In fact the first mention of Nebbiolo is found in texts dating all the way back to 1266 making it very much a grape of the Middle Ages. The grape is so old that researchers have concluded its parents are extinct; its origins lost in the scented-mists of time.

Piemonte is considered the homeland of this revered grape; here three-quarters of the world’s plantings fan over the best hillside slopes, producing fragrant, soul-stirring, age-worthy wines, under the designations Barolo or Barbaresco. The main difference between the two is the soils the vineyards are planted on, Barolo generally on the less fertile type with wines that display higher tannins.

Though for all its nuance and beauty Nebbiolo is hardly seen growing outside of Italy. In reference book ‘Wine Grapes’ this is penned:

“The siren like beauty and power of the finest examples of Barolo or Barbaresco have lured producers around the world to try their hand and their land with this variety, just as they have done with Pinot Noir but so far on a much more limited scale. It is not a very adaptable variety, its all-important fragrance is decidedly fragile, and it has shown a marked reluctance to travel.”

Piemonte is considered the homeland of this revered grape; here three-quarters of the world’s plantings fan over the best hillside slopes, producing fragrant, soul-stirring, age-worthy wines, under the designations Barolo or Barbaresco. The main difference between the two is the soils the vineyards are planted on, Barolo generally on the less fertile type with wines that display higher tannins.

Though for all its nuance and beauty Nebbiolo is hardly seen growing outside of Italy. In reference book ‘Wine Grapes’ this is penned:

“The siren like beauty and power of the finest examples of Barolo or Barbaresco have lured producers around the world to try their hand and their land with this variety, just as they have done with Pinot Noir but so far on a much more limited scale. It is not a very adaptable variety, its all-important fragrance is decidedly fragile, and it has shown a marked reluctance to travel.”

Maybe it needed Italian hands to travel in; or at least to ride shotgun with the legend of the she-wolf. As Roman native Sandro Arcangeli did; the stories of his people dancing in his blood while making his home across Southern Africa.

For his Nebbiolo from Arcangeli Wines he was inspired by the most famous of all Roman myths, the story of Romulus and Remus. Abandoned, the twins were said to be suckled by a she-wolf as babies. Romulus went onto establish the great empire of Rome, from where the Arcangeli family originates.

Far, far south of the Vatican, along a winding road in Bot River, South Africa – Sandro now resides at his small wine estate, and has given the name Romulus to his South African grown Nebbiolo.

I find him and winemaker Krige Visser in the tasting room, straight off the tar road, an important detail: Sandro tells me growing up they had a dirt road to their home – something he promised he’d never have again. His voice is thick and musical with an Italian accent massaged with a lilt of Africana.

The valley drops off around us, a series of golden hills under an oppressively blue sky, birds of prey wheeling in the wind.

Sandro’s family emigrated when he was 16 to what was then Rhodesia, his father worked in construction. A colourful life followed, from competitive ballroom dancing and running nightclubs in Johannesburg, to making Lesotho his home for many years – before purchasing this winery and employing the sage-like winemaker Krige.

Because of the size, four-hectares of organic vineyards, Krige scours the Western Cape for grapes to supplement the range. For the Romulus the vineyard is in the Breede Valley and is called Dagbreek. The wine flashes pale and ephemeral in the glass, faded red velvet going orange at the rim. Its light colour is one of its famous attributes as it belies the power and longevity of the wine.

I find him and winemaker Krige Visser in the tasting room, straight off the tar road, an important detail: Sandro tells me growing up they had a dirt road to their home – something he promised he’d never have again. His voice is thick and musical with an Italian accent massaged with a lilt of Africana.

The valley drops off around us, a series of golden hills under an oppressively blue sky, birds of prey wheeling in the wind.

Sandro’s family emigrated when he was 16 to what was then Rhodesia, his father worked in construction. A colourful life followed, from competitive ballroom dancing and running nightclubs in Johannesburg, to making Lesotho his home for many years – before purchasing this winery and employing the sage-like winemaker Krige.

Because of the size, four-hectares of organic vineyards, Krige scours the Western Cape for grapes to supplement the range. For the Romulus the vineyard is in the Breede Valley and is called Dagbreek. The wine flashes pale and ephemeral in the glass, faded red velvet going orange at the rim. Its light colour is one of its famous attributes as it belies the power and longevity of the wine.

“You’ve got to trust your gut in winemaking. I look for the soul of the grape,” shared Krige. He prefers a hands-off approach in the winery, employing native yeasts for wild ferments and maturation in old oak barrels and eggs.

“This is a South African interpretation,” said Sandro, his voice gravelly. “Nebbiolo doesn’t have to be overtly tannic or acidic, you don’t have to push the grape to a grandiose expression, treat it as it is.

We talk about how ‘nebbia’ in Nebbiolo means fog. My mind drifts to the image of Piemonte’s famously fog-laden hills, widely believed to be the reason for the grape’s name.

“Though we do press it in the traditional way, with our feet! This includes all the skins and stalks, as the grapes are whole bunch pressed. In Italy we would never do this.”

“We’re fighting tannin with tannin,” added Krige, a reference to the intact stalks.

Half spirit, pale and transcendent; half flesh, tannic and firm, the savoury 2016 has netted in that all-important fragrance, the nostalgic musk of summer roses, deepening into tomato vine heavy with ripening fruit. Tarry, sweet red berries, dusted with cinnamon and turned earth, the finish like kirsch cherry liqueur, though ending dry and resolute, the tannins a shadow fortress, caging it all in.

“Not so, most people think that,” explained Krige. “It’s actually named for the thick natural bloom covering the ripe berries, as if covered in fog.”

“This is a South African interpretation,” said Sandro, his voice gravelly. “Nebbiolo doesn’t have to be overtly tannic or acidic, you don’t have to push the grape to a grandiose expression, treat it as it is.

We talk about how ‘nebbia’ in Nebbiolo means fog. My mind drifts to the image of Piemonte’s famously fog-laden hills, widely believed to be the reason for the grape’s name.

“Though we do press it in the traditional way, with our feet! This includes all the skins and stalks, as the grapes are whole bunch pressed. In Italy we would never do this.”

“We’re fighting tannin with tannin,” added Krige, a reference to the intact stalks.

Half spirit, pale and transcendent; half flesh, tannic and firm, the savoury 2016 has netted in that all-important fragrance, the nostalgic musk of summer roses, deepening into tomato vine heavy with ripening fruit. Tarry, sweet red berries, dusted with cinnamon and turned earth, the finish like kirsch cherry liqueur, though ending dry and resolute, the tannins a shadow fortress, caging it all in.

“Not so, most people think that,” explained Krige. “It’s actually named for the thick natural bloom covering the ripe berries, as if covered in fog.”

︎︎︎

Sandro Arcangeli, Photographer:Hanfred Rauch

Styling: Alwijn Burger

And it is true that grape names are more likely connected to its characteristics than climatic conditions. Like the grape Roussanne, which blushes rosily as it ripens. Regardless, because of this prevailing belief that Nebbiolo does well in the mist, it is often planted in such sites, and synergistically does ripen well, perhaps because with its thin skins it likes things a bit cooler.

Proof of this is the Dagbreek vineyard, which is part of the Du Toitskloof holdings, from where they also make a single varietal Nebbiolo – a dusky rendition of dark flora and concentrated cherry.

Speaking to marketing director Ed Beukes

about it, he shared this: “Philip Jordaan, who was the winemaker before Shawn Thomson, had actually visited the north of Italy around 20-years-ago and when he saw the dense fog in the vineyards, he was reminded of the foggy winters in the Breedekloof. There are some patches at Dagbreek where it becomes nearly impossible to see five metres ahead of you.”

Nebbiolo vineyards are few and far between. The oldest existing one was planted in 1993 in the Cape South Coast, likely from cuttings procured on a trip to North Italy in the late 80s by Peter Finlayson (Bouchard Finlayson) and Herman Hanekom (Steenberg). Both planted respective vineyards, Bouchard Finlayson also in 1993 and Steenberg in 1994. Finlayson’s grapes made their way into a French/Italian blend, the Hannibal, which was a runaway success and a total maverick of its time.

Speaking of pioneers, in South Africa we often sing the praises of the Huguenots, indebted to their arrival by boat, a vine cutting under the one arm, and a bible under the other. Italians too have a rich, though unsung, history in our winelands.

Speaking to marketing director Ed Beukes

about it, he shared this: “Philip Jordaan, who was the winemaker before Shawn Thomson, had actually visited the north of Italy around 20-years-ago and when he saw the dense fog in the vineyards, he was reminded of the foggy winters in the Breedekloof. There are some patches at Dagbreek where it becomes nearly impossible to see five metres ahead of you.”

Nebbiolo vineyards are few and far between. The oldest existing one was planted in 1993 in the Cape South Coast, likely from cuttings procured on a trip to North Italy in the late 80s by Peter Finlayson (Bouchard Finlayson) and Herman Hanekom (Steenberg). Both planted respective vineyards, Bouchard Finlayson also in 1993 and Steenberg in 1994. Finlayson’s grapes made their way into a French/Italian blend, the Hannibal, which was a runaway success and a total maverick of its time.

Speaking of pioneers, in South Africa we often sing the praises of the Huguenots, indebted to their arrival by boat, a vine cutting under the one arm, and a bible under the other. Italians too have a rich, though unsung, history in our winelands.

Many Italian prisoners of World War II were sent here, men who were responsible for carving through mountains to give us Chapman’s Peak and Bainskloof Pass; and who worked vineyards while waiting out sentences. For a glance back into the past go take a look at the murals Wederom winery in Robertson by POW Giovanni Salvadori, one of the few remnants of this time.

Today the Italian influence is still felt with family run estates, such as the Bottegas, who produce the Idiom 900 Series Nebbiolo from a low yielding Stellenbosch vineyards; all silk and power.

Close-by at Morgenster Wine & Olive Estate, founder the late Giulio Bertrand had imported two clones developed by the University of Torino. The family released their maiden single-vineyard Nebbiolo, the Nabucco in 2006.

There are other examples too, such as at Anura in the Simonsberg Paarl region, or in the cool locales of Domaine Des Dieux in the Hemel-en-Aarde and soon Iona in Elgin. A small chorus in support of the historic cultivar seems to be gathering, like archangels at dusk.

I painted this wing-tipped vision on the backs of my eyelids as I sat and watched that startling blue sky begin to smudge to pink. The flavour of iodine, the tang of blood remained on my tongue, a legacy of the Nebbiolo, the glass now emptied.

Today the Italian influence is still felt with family run estates, such as the Bottegas, who produce the Idiom 900 Series Nebbiolo from a low yielding Stellenbosch vineyards; all silk and power.

Close-by at Morgenster Wine & Olive Estate, founder the late Giulio Bertrand had imported two clones developed by the University of Torino. The family released their maiden single-vineyard Nebbiolo, the Nabucco in 2006.

There are other examples too, such as at Anura in the Simonsberg Paarl region, or in the cool locales of Domaine Des Dieux in the Hemel-en-Aarde and soon Iona in Elgin. A small chorus in support of the historic cultivar seems to be gathering, like archangels at dusk.

I painted this wing-tipped vision on the backs of my eyelids as I sat and watched that startling blue sky begin to smudge to pink. The flavour of iodine, the tang of blood remained on my tongue, a legacy of the Nebbiolo, the glass now emptied.

While Steenberg produces a single varietal wine from the original vineyard as well as one they planted in 2007. It’s one of my favourite South African expressions, such clarity of fruit, bright tomato, tangy cranberry; fresh and vital with an undercurrent of truffle, an edge of delectable decay to its sunshiny nature.︎

![]()

9.

Seeking new heights

This article originally appeared on Michael Fridjohn

We just have to look to the soaring vineyards of Argentina to know that viticulture is literally on the rise. Many of the country’s vines are grown at dizzying heights, from 1000m and above to even as high as 3300m. It’s neighbour Chile also has high-flung pockets, in the Elqui Valley for example producers are even experimenting with aromatic varieties such as riesling.

There’s no doubt that as the world warms we will begin to look skyward: it’ll be something of a gold rush to claim the cooler, higher sites as climatic doom starts to descend. Climate change is without a doubt the most burning issue facing viticulture, though extreme vineyards are not just an escape route – it’s also a question of style. Can there be more site-expressive wines than grapes grown almost touching the heavens?

When planted at height these vineyards are firmly continental in climate as opposed to those with ocean views moderated by the big blue. Grapes in alpine vineyards ripen later, concentrating flavour compounds. They also experience high diurnal swings (hot days, cold nights) that magic acidity retainer, plus the grapes receive more solar radiation than their grounded counterparts, ramping up phenols and anthocyanin, thickening skins and deepening colour.

Celebrated winemaker Charles Hopkins is no stranger to aiming high. Cellar master at De Grendel owned by the Graaff family he works with a variety of other sites too. Recently released the Op die Berg Syrah 2019 is the third addition to De Grendel’s Op die Berg range, which also incorporates a pinot and chardonnay.

There’s no doubt that as the world warms we will begin to look skyward: it’ll be something of a gold rush to claim the cooler, higher sites as climatic doom starts to descend. Climate change is without a doubt the most burning issue facing viticulture, though extreme vineyards are not just an escape route – it’s also a question of style. Can there be more site-expressive wines than grapes grown almost touching the heavens?

When planted at height these vineyards are firmly continental in climate as opposed to those with ocean views moderated by the big blue. Grapes in alpine vineyards ripen later, concentrating flavour compounds. They also experience high diurnal swings (hot days, cold nights) that magic acidity retainer, plus the grapes receive more solar radiation than their grounded counterparts, ramping up phenols and anthocyanin, thickening skins and deepening colour.

Celebrated winemaker Charles Hopkins is no stranger to aiming high. Cellar master at De Grendel owned by the Graaff family he works with a variety of other sites too. Recently released the Op die Berg Syrah 2019 is the third addition to De Grendel’s Op die Berg range, which also incorporates a pinot and chardonnay.

The grapes are mountain-grown 1000 metres above sea level in the Witzenberg’s Ceres Plateau on a farm called Rietfontein, which is owned by Robert Graaff, brother of De Grendel’s late owner Sir De Villiers Graaff.

In the winter snow blankets the landscape, locking the vines into restful, icy dormancy. The Op die Berg Syrah 2019 almost tastes of cold: limpid and woven through with white peppery spice, sour cherries and cranberries. There’s a crystallising effect on the palate as the acidity shapes and facets its liminal purity. There’s just a hint of mushroomy decay, something wicked in its snowy innocence. It’s a wine to ruby the blood.

There are more lofty sites to come for Hopkins, with planting programmes headed by viticulturist Stephan Joubert being planned for isolated, mountainous sites in the Hex River and Koo valleys. Along with the prerequisite chardonnay and pinot noir, pinotage is said to be on the cards too.

Though of course the original high and dry

pioneers, Cederberg Wines lay claim to Cape’s highest lying vineyards, at 1063m. The now sixth-generation farm is situated in the Cederberg Wilderness Area, owned by David Nieuwoudt. The first high-altitude vintage was circa 1977 and the estate continues to produce award-winning wines to this day.

Roving producer Jean Smit of Damascene also seeks out these rocky sites for his Cederberg Syrah, from one of the oldest farms in the Cederberg, which dates back to 1790. The syrah he sources from a vineyard planted in 2006.

![]()

There was a time when producers would barely consider quality wines coming from ‘anderkantdieberg’, and now the Breedekloof Valley is more than proving its mettle with its distinctive wines, the accolades pouring in like snow melt. But now it seems we’ve gone from the ‘other side of the mountain’ and trekked much further into rocky corridors.

pioneers, Cederberg Wines lay claim to Cape’s highest lying vineyards, at 1063m. The now sixth-generation farm is situated in the Cederberg Wilderness Area, owned by David Nieuwoudt. The first high-altitude vintage was circa 1977 and the estate continues to produce award-winning wines to this day.

Roving producer Jean Smit of Damascene also seeks out these rocky sites for his Cederberg Syrah, from one of the oldest farms in the Cederberg, which dates back to 1790. The syrah he sources from a vineyard planted in 2006.

As our winemakers’ ambitions continue to soar, perhaps this bodes the end of the Cape’s monopoly on winegrowing. I can’t help but imagine vines rooted in the snowy peaks of Lesotho or even fanned across the mythic monolith of the Drakensberg. It seems the sky’s the limit after all.︎

8.

South African Wine Legend: John Loubser

This article originally appeared on Wines of South Africa

“We spend so much time looking for fossils,” says Cap Classique specialist John Loubser, unpacking an assortment of rocks. We’re tucked away in a corner at Steenberg, overlooking the cellar he spent 15 years in as cellar master and general manager. He left in 2017 to devote himself to Silverthorn full-time, his family’s boutique estate in Robertson.

![]()

With bright eyes he passes over a flat stone – there is no mistaking the fan-like shapes of a dozen seashells pressed into the rock, a fossil from the antediluvian ocean that once covered Robertson. It’s a terrestrial reminder that it’s the only region in South Africa with significant limestone deposits, much like the kimmeridgian soils of Champagne, making it our holy ground for the production of sparkling wine.

With bright eyes he passes over a flat stone – there is no mistaking the fan-like shapes of a dozen seashells pressed into the rock, a fossil from the antediluvian ocean that once covered Robertson. It’s a terrestrial reminder that it’s the only region in South Africa with significant limestone deposits, much like the kimmeridgian soils of Champagne, making it our holy ground for the production of sparkling wine.

“I was annoyed there are no dinosaur fossils,” John laments. “The reason they aren’t is that the soils in Robertson are 400-million years old, which means they pre-date them.”

“Now look at this,” he says passing over a smaller rock. More evidence of the ancient ocean with its millennia-old imprint of a small wave cresting. “We found this trace fossil behind our cellar, we think it’s a pectoral fin.”

If the sky could

dream, would it

dream of dragons?

This obsession with fossils led him to naming his new bubbly River Dragon NV, ‘if we can’t have dinosaurs, we can have dragons!’ John hands me a glass of it and explains he named it after the legend of draco Africanus, who was said to skywrite with smoke.

In a trailblazing move he made the River Dragon from 38-year-old vine colombard, wild fermented in acacia barrels (a nod to Silverthorn…), then 12 months on the lees.

“It has this incredible acidity,’ he enthuses. And it does, rapier quick right across the palate, a steel rod for the fruit to hang from: pear, bergamot, green mango, guava leaf. Refreshing and full of life. Much like its maker.

“Most nights I share a bottle of bubbly with my wife Karen,” he shares. The devoted couple live on the farm. Their children Faine and Tivon are in their early twenties, Faine is a UCT graduate in Film & Media as well as free diver; in fact she worked on Oscar-winning documentary My Octopus Teacher, while son Tivon is studying a Bachelor of Business Science.

When not making bubbles, you’ll find John in nature, practising longbow archery, doing carpentry using antique tools, or spending time with his beloved Rottweilers.

In 2019 the Loubsers built a specialised Cap Classique cellar, which is situated just 40 metres away from a river, which is home to Cape clawless otters. The first vintage he made on the farm was in 2020, prior to that he made Silverthorn at Steenberg, The Green Man’s inaugural vintage was in 2004, officially launching the brand in 2006.

Wine has been a constant theme in his life. His father was a Windhoek hotelier who instilled the passion in him. “I grew up among wine pallets.”

“Most nights I share a bottle of bubbly with my wife Karen,” he shares. The devoted couple live on the farm. Their children Faine and Tivon are in their early twenties, Faine is a UCT graduate in Film & Media as well as free diver; in fact she worked on Oscar-winning documentary My Octopus Teacher, while son Tivon is studying a Bachelor of Business Science.

When not making bubbles, you’ll find John in nature, practising longbow archery, doing carpentry using antique tools, or spending time with his beloved Rottweilers.

In 2019 the Loubsers built a specialised Cap Classique cellar, which is situated just 40 metres away from a river, which is home to Cape clawless otters. The first vintage he made on the farm was in 2020, prior to that he made Silverthorn at Steenberg, The Green Man’s inaugural vintage was in 2004, officially launching the brand in 2006.

Wine has been a constant theme in his life. His father was a Windhoek hotelier who instilled the passion in him. “I grew up among wine pallets.”

“As a young kid I went with him many times to the Nederburg Auction, I think I was six the first time.”

He was schooled in the Cape, boarding at Bishops. After matriculating he studied architecture. Which he says he did not complete due to ‘lack of mental stimulation’. This was followed by two years of military service.

It was then back to the wild seas and sand dunes of his home, where he spent two years diving for diamonds off Namibia’s Skeleton Coast. Somewhere along the way he met Karen in the Cape at a beach party. “She told me later that she decided that day she was going to marry me.”

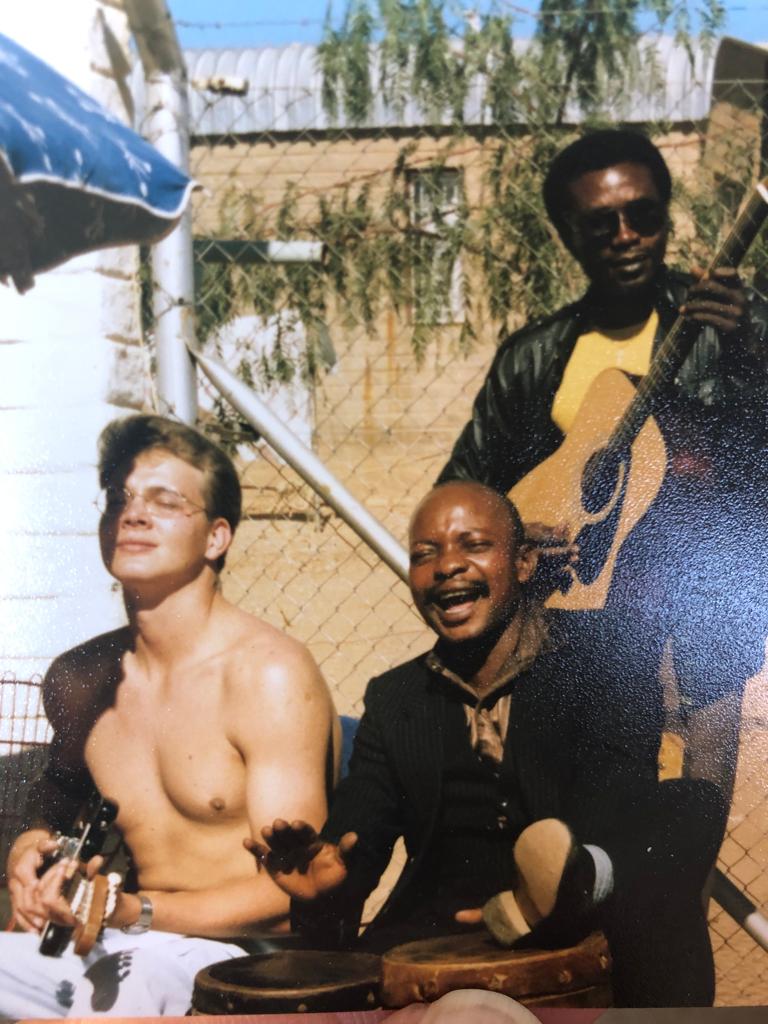

![]()

He was schooled in the Cape, boarding at Bishops. After matriculating he studied architecture. Which he says he did not complete due to ‘lack of mental stimulation’. This was followed by two years of military service.

It was then back to the wild seas and sand dunes of his home, where he spent two years diving for diamonds off Namibia’s Skeleton Coast. Somewhere along the way he met Karen in the Cape at a beach party. “She told me later that she decided that day she was going to marry me.”

︎︎︎

It was Karen’s family who in 1976 purchased the farm they now call home; after they met she took him there to meet them. John says it occurred to him then that he’d ‘better go study winemaking’.

But before wine got its hooks in the pair spent a year backpacking across Europe. Until finally fate had its way and at the age of 25 he enrolled at Elsenburg, graduating as the Dux student.

Very quickly he landed a plum position as winemaker for Môreson. Then wanting to be closer to home he did a stint at de Wetshof in Robertson followed by a couple of years working at Graham Beck’s Robertson cellar with Pieter Ferreira.

In 2001 he became the cellar master at Steenberg. He won the prestigious ‘Dinners Club Wine Maker of the Year’ in 2003 and has been a member of the prestigious Cape Winemakers Guild since December 2004.

“You experience bubbly with all of your senses – it’s world’s apart from any other wine.” He holds up his glass to his ear, I mirror him, appreciating the fizz, crackle and pop. “It’s the only wine you can actually hear.”

“There’s another reason why people are drawn to champagne – why it’s been used for celebrations through the ages. When you pop a cork negative ions are released.”

But before wine got its hooks in the pair spent a year backpacking across Europe. Until finally fate had its way and at the age of 25 he enrolled at Elsenburg, graduating as the Dux student.

Very quickly he landed a plum position as winemaker for Môreson. Then wanting to be closer to home he did a stint at de Wetshof in Robertson followed by a couple of years working at Graham Beck’s Robertson cellar with Pieter Ferreira.

In 2001 he became the cellar master at Steenberg. He won the prestigious ‘Dinners Club Wine Maker of the Year’ in 2003 and has been a member of the prestigious Cape Winemakers Guild since December 2004.

The only wine you can hear

“You experience bubbly with all of your senses – it’s world’s apart from any other wine.” He holds up his glass to his ear, I mirror him, appreciating the fizz, crackle and pop. “It’s the only wine you can actually hear.”

“There’s another reason why people are drawn to champagne – why it’s been used for celebrations through the ages. When you pop a cork negative ions are released.”

These invisible molecules (which have gained or lost an electrical charge) are found where there are moving liquids under pressure –like the ocean or a waterfall – and are said to promote endorphins and relieve stress.

“Watch for the wisp,” John says easing the cork out of The Genie, a plume of smoke slides out; he trails his finger through it, doing his own version of dragon skywriting. “Those are the negative ions.”

The Genie released into my glass is light, pearlescent pink. This is no tannic Australian sparkling shiraz; light-footed and popping with raspberries and cherries, with a hint of spice. He says he handles it very gently in the cellar, whole-bunches, soft pressing, so much so that the resulting wine is white; he achieves the final colour with dosage.

Also in the line-up is the Jewel Box 2017 (a cuvée of chardonnay and pinot noir), which scored an impressive 96-points in the Tim Atkin MW 2021 South Africa Special Report. His other Cap Classiques also garnered excellent scores.

The Jewel Box spent 45 months on the lees and is richly autolytic for it, all those toasty, nutty flavours, creamy, beautifully so, then super dry on the palate with a savoury finish. Delicious.

“Watch for the wisp,” John says easing the cork out of The Genie, a plume of smoke slides out; he trails his finger through it, doing his own version of dragon skywriting. “Those are the negative ions.”

The Genie released into my glass is light, pearlescent pink. This is no tannic Australian sparkling shiraz; light-footed and popping with raspberries and cherries, with a hint of spice. He says he handles it very gently in the cellar, whole-bunches, soft pressing, so much so that the resulting wine is white; he achieves the final colour with dosage.

Also in the line-up is the Jewel Box 2017 (a cuvée of chardonnay and pinot noir), which scored an impressive 96-points in the Tim Atkin MW 2021 South Africa Special Report. His other Cap Classiques also garnered excellent scores.

The Jewel Box spent 45 months on the lees and is richly autolytic for it, all those toasty, nutty flavours, creamy, beautifully so, then super dry on the palate with a savoury finish. Delicious.

Elegant, fine and long, tasting the wine is a bit like walking through a sun-dappled forest. Prismatic and peaceful.

“At Silverthorn we try to do everything as sustainable and organic as possible, from cover crops to interplanting,” he elaborates. “We’re trying to create happy vineyards.

“It’s been a long dream to get here and we have travelled many paths, but the one thing we’ve always had was patience.

“We knew it would all work out, when the time was right.”

Time and patience – two of the most important words in the making of fine Cap Classique.︎

“At Silverthorn we try to do everything as sustainable and organic as possible, from cover crops to interplanting,” he elaborates. “We’re trying to create happy vineyards.

“It’s been a long dream to get here and we have travelled many paths, but the one thing we’ve always had was patience.

“We knew it would all work out, when the time was right.”

Time and patience – two of the most important words in the making of fine Cap Classique.︎

7.

The spirit of genius walks in South Africa’s vineyards

This article originally appeared on wine.co.za

Romans had their own concept of terroir, calling it genius loci, the spirit or genius of the place. This Latin phrase is equally apt for South Africa’s current winemaking zeitgeist: there’s an unstoppable force moving through our regions, much like the winds that churn off the coast. Energy, dynamism, innovation and camaraderie are all words to describe the current spirit of South African winemaking.

As if to experience this modern-day milieu in technicolor I recently had lunch with three of South Africa’s most exciting winemakers: Tim Atkin’s Winemaker of The Year Peter-Allan Finlayson of Crystallum and Gabriëlskloof, John Seccombe of Thorne & Daughters and Marelise Niemann of Momento.

![]()

As if to experience this modern-day milieu in technicolor I recently had lunch with three of South Africa’s most exciting winemakers: Tim Atkin’s Winemaker of The Year Peter-Allan Finlayson of Crystallum and Gabriëlskloof, John Seccombe of Thorne & Daughters and Marelise Niemann of Momento.

Swathes of butter-coloured canola fields led the way to Gabriëlskloof. It was one of those heady spring days – everything felt plumped with life, the sky bluer, the clouds fatter, the air had a crystalline quality, fresh and new. It must have been a fruit day so expressive were the wines spread out over the table.

As I sat there in that limpid sunshine with a glass of the Agnes 2020, the epitome of modern Cape chardonnay, I realised something we often fail to in present moments. 20 years from now if I had to look back to this day I’d see it clearly – we were right in the thick of it, the vanguard of the new South African wine epoch. The wave is currently cresting, opportunity is everywhere – and winemaking talent is almost profligate in its excess.

Peter-Allan agrees with me: “I really do think we are in a golden age of South African wine. We went from being ugly ducklings to the most exciting New World region in a very short period of time. There are many reasons for this. One of them being visionary new producers whom apply old world maxims of marrying cultivar to place as well as valuing the age of vineyards, this has seen the quality of our wines rocket up.”

Winemaker of The Year

Third-generation winemaker Finlayson comes from famous stock; his father is Peter Finlayson of Bouchard Finlayson, one of the front-runners of pinot noir in the Hemel-en-Aarde. Like his dad, he also has a deft touch with the Burgundian grape.

The proof is in his pinots. Tasting them side-by-side, Finlayson has managed to capture two distinct expressions; the Bona Fide has a lighter touch, fragrant with cherry blossoms, autumn leaves, white mushroom. The palate is serene and long. It’s counterpart the Cuvée Cinéma is deeper, more structured. Black fruited and taut, a layered density built to last. Both wines are majority whole bunch, adding lift and brightness.

Chardonnay is the other focus for Crystallum (a project he runs with his brother Andrew, who is on the viticultural side). As mentioned above the Agnes is firmly one of the Cape’s top chardonnays – a modern classic. Finlayson also makes a more leftfield one. The debut vintage of Ferrum Chardonnay comes from a single vineyard on Shaw’s Mountain, Crystallum’s own vineyards, which are located just beyond the Hemel-en-Aarde.

Wild ferment and whole-bunch pressed, the wine was then matured for 10 months in 300 and 500-litre barrels, 20% new. It trips the light fantastic, mandarin and kumquat, orange-toned and electric, then high notes of lemon verbena and the dewy, clean scent of lemon leaves washed by rain. Faceted like a jewel on the palate, it’s austere in its brilliance. Crunchy acids pull in every direction: it’s salty, dry, appetising.

Syrah – the key red variety

for

We also tasted his Gabriëlskloof wines. The standouts being his two syrahs in the Landscape series.

It's brave new world for syrah in South Africa, it grows well in a variety of terroirs, the barrier to entry is lower (older oak is preferred to new oak, the latter being an economic concern) and the wines can be very expressive of site.

Finlayson elaborated: “Syrah works across the Western Cape, while something like pinot only works in a few select places, syrah is much more versatile. Syrah fell out of favour with wine lovers because, like chardonnay, the wines

were being made in a generic, ripe and oaky style. Then along came the Eben Sadie, Adi Badenhorst and the Mullineuxs who showed the country and the world that we could make extraordinary, elegant syrahs in warm, rugged conditions.

Syrah – the key red variety

for

South Africa?

We also tasted his Gabriëlskloof wines. The standouts being his two syrahs in the Landscape series.

It's brave new world for syrah in South Africa, it grows well in a variety of terroirs, the barrier to entry is lower (older oak is preferred to new oak, the latter being an economic concern) and the wines can be very expressive of site.

Finlayson elaborated: “Syrah works across the Western Cape, while something like pinot only works in a few select places, syrah is much more versatile. Syrah fell out of favour with wine lovers because, like chardonnay, the wines

were being made in a generic, ripe and oaky style. Then along came the Eben Sadie, Adi Badenhorst and the Mullineuxs who showed the country and the world that we could make extraordinary, elegant syrahs in warm, rugged conditions.

︎︎︎

“It feels like it’s easy to make a drinkable, fruit-forward style, but teasing out the really enticing side of syrah requires a special site and very careful handling in the cellar.”

![]()

His two syrahs, Sandstone and Shale, represent the two major soil types at Gabriëlskloof. The sandstone vineyards favouring the more aromatic, floral side of the grape, while the heavier shale soils produce wines with more depth.

His two syrahs, Sandstone and Shale, represent the two major soil types at Gabriëlskloof. The sandstone vineyards favouring the more aromatic, floral side of the grape, while the heavier shale soils produce wines with more depth.

It was in fact a syrah that clinched a perfect 100-point score in Tim Atkin’s 2021 South Africa Special Report, the 2019 Sadie Family Columella. In it Atkin has hailed the grape as the Cape’s most impressive red variety; being responsible for 17 of his 161 wines of the year.

But it’s not just a conversation about syrah - Atkin’s report, and his crowning of Finlayson as Winemaker of the Year, underscores the genius loci of our present time and the producers who are increasingly making wines with a sense of place, done so with a respect and reverence to site.

But it’s not just a conversation about syrah - Atkin’s report, and his crowning of Finlayson as Winemaker of the Year, underscores the genius loci of our present time and the producers who are increasingly making wines with a sense of place, done so with a respect and reverence to site.

English poet Alexander Pope interpreted genius loci as: ‘consult the genius of place in all’. Something Finlayson and his cohorts seem to know intuitively as they continue to bottle the spirit of place for their distinct, truly South African wines.︎

![]()